What is happening to the Argentine economy? An economic miracle or a downward spiral?

It used to be a tradition for many Argentines to take the family on a Friday night to a meat restaurant on the Paraná River embankment and enjoy an asado (meat, sausages and offal grilled over coals). Today, in a country long known for its love of quality meat, this pastime has become unattainable. Instead, Argentines are offered cheap pork and chicken. Just last year, per capita beef consumption in Argentina fell to its lowest level in a century, reports The Washington Post, citing data from the Rosario Chamber of Commerce. In 2024, that figure was 44.8 kg of beef per person, well below the historical average of 72.9 kg — almost half.

The Buenos Aires Times writes: «Beef is becoming increasingly scarce — a luxury for most Argentines, who have cut their meat consumption to the lowest level in a century».

This is true of everything. Last year, industrial activity in Argentina fell by a staggering 9.4% and construction by 27.4% — the worst figures for both sectors in nearly two decades.

At the same time, a cascade of harsh cuts — affecting everything from free cafeterias to bus fare subsidies — has pushed more than five million Argentines below the poverty line.

On January 10, the Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Kristalina Georgieva, described the changes in Argentina’s economic policies over the past year as «the most impressive case in modern history». At a press conference at the IMF headquarters in Washington, Georgieva said that in 2024 «in many countries we have witnessed changes in government policies, and the most impressive example in modern history is Argentina, where the consequences are serious due to the implementation of a reliable stabilization and growth program».

When Milei took office, Argentina’s economy was undoubtedly in dire straits. It had experienced no fewer than six recessions in the previous 12 years. For ten months, it had struggled with soaring triple-digit annual inflation, earning it the dubious distinction of having the highest annual inflation rate in the world. At the beginning of last year, that annual rate was approaching 300%, but it has since fallen and was still a staggering 118% at the end of 2024.

According to Argentine economists, this was due in part to good timing and a «new discovery of America». That was when Vaca Muerta («Dead Cow») — a shale basin in northern Patagonia known only to specialists and the Argentine government, covering an area of 30,000 square kilometers, the world’s second-largest shale gas reserve and fourth-largest shale oil reserve, and one of the largest unconventional oil and gas deposits in the world — went into production. This happened just five months after the inauguration of the first section of the pipeline, named after President Néstor Kirchner.

Milei was lucky. It was he — not his predecessors who discovered these reserves — who was allowed to begin operating and exporting natural gas this year. The irony is that the Néstor Kirchner pipeline received significant government funding, as well as financing from China, and Milei immediately backtracked on his attacks on Beijing. Now he intends to «revive» relations by visiting China this July — if Trump allows it.

Meanwhile, everyone is hailing Argentina’s unpredictable leader, who announced a record trade surplus of $18.9 billion — largely due to the first full year in office for the libertarian president. Last year’s trade surplus surpassed the previous annual record of $16.89 billion set in 2009.

One of the main ways in which Milei reduced inflation was by maintaining an artificially high exchange rate of the Argentine peso against the dollar. He achieves this by removing pesos from the foreign exchange market and maintaining a fixed official exchange rate against the dollar that rises by only 1% per month. An unintended consequence of this policy is that inflation has risen in dollar terms, making Argentina the most expensive country in Latin America in dollar terms.

On the bright side, the decline in industrial activity may have finally bottomed out. According to a report by the National Institute of Statistics and Census (INDEC), Argentina is now producing fewer goods than a year ago. Only 30% of Argentina’s economy remains at the level it was before Milei’s administration. Based on this data, it’s hard to say that Argentina’s economy has fully recovered. However, experts see this as a positive sign — there is a base from which to recover.

The two main sectors that have not only recovered but thrived after Milei took power — finance and mining — are also the two least «productive» sectors of the economy. Not only do they generate little tax revenue, but they also employ relatively few workers (4% of the total). In contrast, the three main sectors currently struggling to survive (construction, industry and trade) account for almost half (44.5%) of the labor market.

And this is where Argentina has hit rock bottom. The good news, once again, is that there is a starting point from which to rise.

Argentina’s largest export market — the source of its foreign exchange — will also need to recover. Delays in payments, bankruptcy filings, temporary production shutdowns and layoffs have prompted about half a dozen companies to announce such measures in the past two weeks alone. Four of them have filed for bankruptcy protection, citing an inability to repay debts totaling about $650 million. Among them are SanCor, one of the country’s best-known dairy producers; Los Grobo Agropecuaria (which handles the collection, marketing and sale of agricultural commodities) and Agrofina (a producer of herbicides, fungicides and insecticides) of the Los Grobo group; and Surcos, which produces fertilizers and herbicides.

Now, Argentina’s industrial sector faces the grim prospect of the Trump administration imposing a 25 percent tariff on all imports of Argentine steel and aluminum. Last year, Argentina exported $600 million worth of steel and aluminum to the U.S., and now its steel industry is already suffering from a sharp downturn in the country’s construction sector.

It’s bottomed out again. But in this particular case, there is no guarantee that the U.S. will extend a helping hand to pull Argentina out of its slump.

In fact, Argentina could be among the countries most affected by the reciprocal tariffs Trump announced last week on goods from any country that imposes tariffs on American products. Trump is imposing reciprocal tariffs for two reasons: Argentina’s tariffs on U.S. goods exceed 10 percent, and Argentina had a $228 million trade surplus with the U.S. last year. «We have a small deficit with Argentina, as we do with all countries», Trump said at a White House press conference, justifying his protectionist policy.

It also doesn’t help that in the last 14 months, at the «urgent request» of the previous U.S. Biden administration, Argentina purchased used F-16 fighter jets from Denmark for hundreds of millions of dollars for Ukraine, provided full support for Israel’s genocide in Gaza in line with the new U.S. Trump administration, established a joint U.S.-Argentinean military base in Ushuaia — at the gateway to Antarctica — and allowed the stationing of U.S. military personnel on the Paraná-Paraguay River, right in the heart of South America’s strategic waterway.

There was hope that these commitments and concessions would help Argentina at least somewhat mitigate the impact of Trump’s tariffs or «appease» the IMF, but it appears that will not be the case.

About a month ago, Milei promised to lift all currency restrictions in Argentina, regardless of whether the IMF provides his country with additional funds. Currency controls are a set of rules that limit capital outflows and the ability to freely exchange — in this case, pesos for dollars and other foreign currencies. Although the IMF has long maintained that Argentina’s currency controls are holding back the economy, there are legitimate concerns that removing them too quickly could trigger a resurgence of the currency and inflation crisis. Moreover, if lifting the controls leads to an outflow of dollars from the central bank, the country will be left without the foreign exchange needed to repay its existing debt to the IMF.

Milei is requesting an additional $11 billion to shore up the country’s foreign exchange reserves. For the IMF, this is a substantial amount — more than a quarter of the Fund’s total lending to other countries. Moreover, the IMF believes that the inadequate Milei’s market reforms may have gone too far, and there is a risk that the world’s largest debtor may once again go bankrupt. But even if the IMF backs Milei, Argentina’s economy might still sink along with those 11 billion dollars.

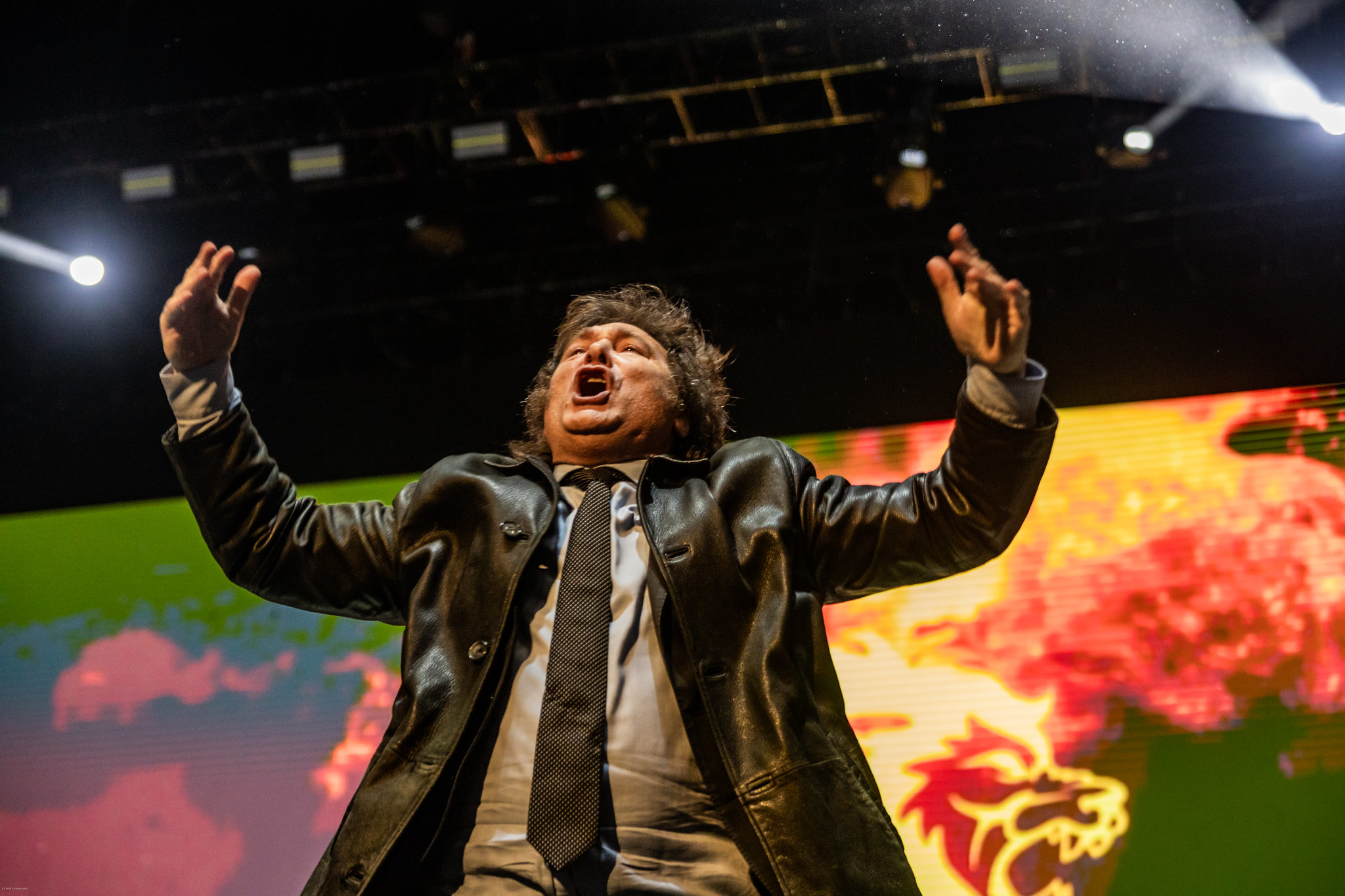

According to financial analysts, the larger the debt, the harder it is for the IMF to solve the debtor’s problems. Milei is taking advantage of this. «I will do everything to end state intervention», he declared, apparently referring to his own government.

He is ready to take a chainsaw and cut up the raft on which Argentina is floating. Reaching the bottom to push off and rise again is a good idea — but a risky one.