Israel's attack on Lebanon has increased the risk of war spreading throughout the Middle East.

There is particular concern about Syria. Will it be drawn into the conflict? And what could be the consequences, especially for Russia?

Israeli attacks on targets in Syria have long become routine. The IDF regularly bombs military installations in the neighboring country under the pretext of the presence of Iranian military forces, weapons depots and training bases on Syrian territory. Allegedly, all this is used to support and strengthen the Lebanese Hezbollah.

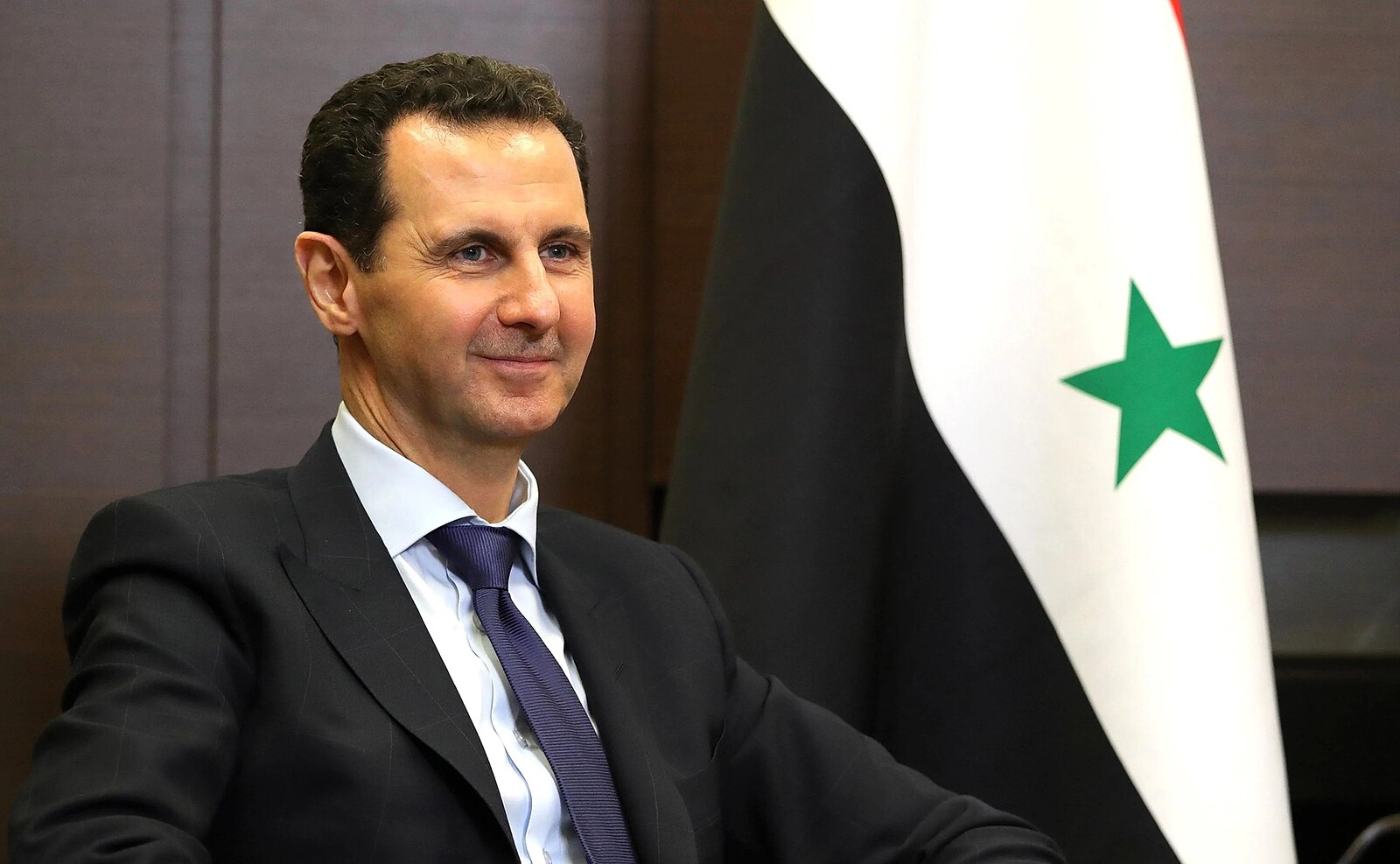

Meanwhile, official Damascus has refrained from getting involved in the conflicts in Gaza and Lebanon. The government of Bashar al-Assad is doing everything it can to avoid being suspected of active anti-Israeli actions and to avoid incurring the wrath and retaliation of Tel Aviv (and, by extension, Washington). Even an incursion by Israeli forces across the Syrian border near Quneitra failed to provoke a symbolic response from the SAR.

This is understandable: Syria has yet to recover from years of civil war, the central government does not control the entire country, the army is weak, and its attention is diverted to fighting terrorist forces.

Russia is also likely to play a key role in determining Syria’s position. Moscow clearly has no interest in destabilizing the SAR, where Russian bases and military contingents are stationed. In the midst of the ongoing military operation in Ukraine, the emergence of a new hotspot in the Middle East requiring Russia’s military involvement is entirely undesirable.

In principle, it can be assumed that Israel has no interest in expanding military operations into Syrian territory. Tel Aviv does not tolerate an Iranian presence in Syria and has no direct claims against the Assad regime. Accordingly, if the Iranians were to withdraw from Syria and the Syrian transit of aid to the Lebanese Hezbollah were to end, the threat of war would diminish.

Damascus appears to be thinking along similar lines: according to many observers, the Syrians are trying to gradually free themselves from the tight grip of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which has gone from being an indispensable ally in the fight against terrorists and the armed opposition to a constant risk factor.

This is where the problems begin. The fact is that withdrawal from Syria is unacceptable to Iran. Too much effort and resources have been invested in establishing a foothold here that provides access to the Mediterranean Sea. For the IRGC, abandoning this foothold would be a strategic defeat that would undermine its status within the Islamic Republic. No one in Tehran would make such a decision without the approval of the IRGC leadership. This means that Iran is likely to defend its presence in Syria at all costs, giving Israel a perfect reason to view Syria as the next strategic target in the current conflict.

Against this background, the warning issued by Turkish President Erdogan a few weeks ago becomes more understandable: he declared that Israel’s invasion of Lebanon posed a direct threat to Turkey. This statement was actively echoed by the authorities in Ankara.

One might ask what kind of threat there could be with Syria between Israel and Turkey. Of course, there are extremist politicians in Israel who speak enthusiastically about the creation of a «Greater Israel» encompassing almost the entire Middle East. But even they do not talk about invading Anatolia.

Nevertheless, Erdogan’s statements cannot be called unfounded. If Iran insists on maintaining its presence in Syria, the risk of the war spilling over into Syrian territory will persist and increase. If Syria becomes a battleground between the IDF and the IRGC, it will pose a direct threat to the security of Anatolia. This would lead to new waves of refugees and terrorists of all kinds flooding into the region. In such a case, Turkey would have to take measures and at least expand the «safe zone» in northern Syria.

Such developments are unlikely to be unacceptable to Ankara. It seems that Turkey would not object to the Iranians being expelled from the region by the Israelis, especially if this provides an opportunity for Turkish occupation of a significant part of Syria (this fits well with the logic of Iranian-Turkish rivalry). An additional bonus could be the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime, which has too proudly rejected Erdogan’s offers to normalize relations. In the long run, all this would create favorable conditions for Turkish-Israeli negotiations on the future of the entire Levant, with Iran in the background.

The scenario described poses a threat to Iran’s interests and carries significant risks for Russia. First, under the current circumstances, Moscow is unlikely to be willing to step in as Bashar al-Assad’s savior, as it did in 2015. Of course, it will make every effort (and undoubtedly already is making every effort) to prevent Israel from launching a full-scale aggression against Syria. Likewise, it is likely to work with Iran to persuade it not to provoke Israel. However, Tel Aviv and Tehran are teetering on the brink of uncontrolled escalation and could at any moment plunge into direct conflict, at which point Russia’s voice would no longer be heard.

Second, Moscow and Tehran are currently on the verge of signing a «major» «strategic» agreement. It cannot be ruled out that the Iranians will insist on including a legally binding military alliance. However, this would mean that our country would automatically be drawn into the Iran-Israel conflict, especially in Syria. This is unacceptable for Russia. However, the Kremlin’s refusal to make such commitments could jeopardize the conclusion of the long-awaited «strategic» agreement and alienate Iran — just as it is ready to declare itself a missile-nuclear power.

Third, in such a scenario, Russia’s interests in Syria will become critically dependent on Turkey. Maintaining a Russian presence in Syria amid constant Iranian-Israeli escalation and inevitable mutual provocations — while ensuring non-involvement in the growing conflict — would be extremely difficult to do alone. An ally would be needed, and in the Syrian theater this role could only be played by Turkey. In the short term, such a solution might solve the current problems, but strategically it seems disadvantageous, as it would unduly strengthen Turkey’s role in Russia’s Middle East policy. Besides, Turkey is a NATO member. Moreover, the government in Turkey will change in the near future, and no one can predict the quality of Russian-Turkish relations after Erdogan.

Russia should make every effort to avoid such a development. It seems that the key to this lies in a firm response to provocations (which are already visible, especially from Israel). It is crucial to avoid being drawn into the conflict between Israel and Iran, as President Putin has already stated, saying that Russia does not interfere in the relations between Iran and Israel. As for Turkey, it seems advisable to focus cooperation with Turkey on solving the problems in northern Syria and fighting terrorist groups there. In addition, a key direction should be to promote rapprochement between Ankara and Damascus, so that Turkey assumes part of the responsibility for the stability of the current Syrian regime.