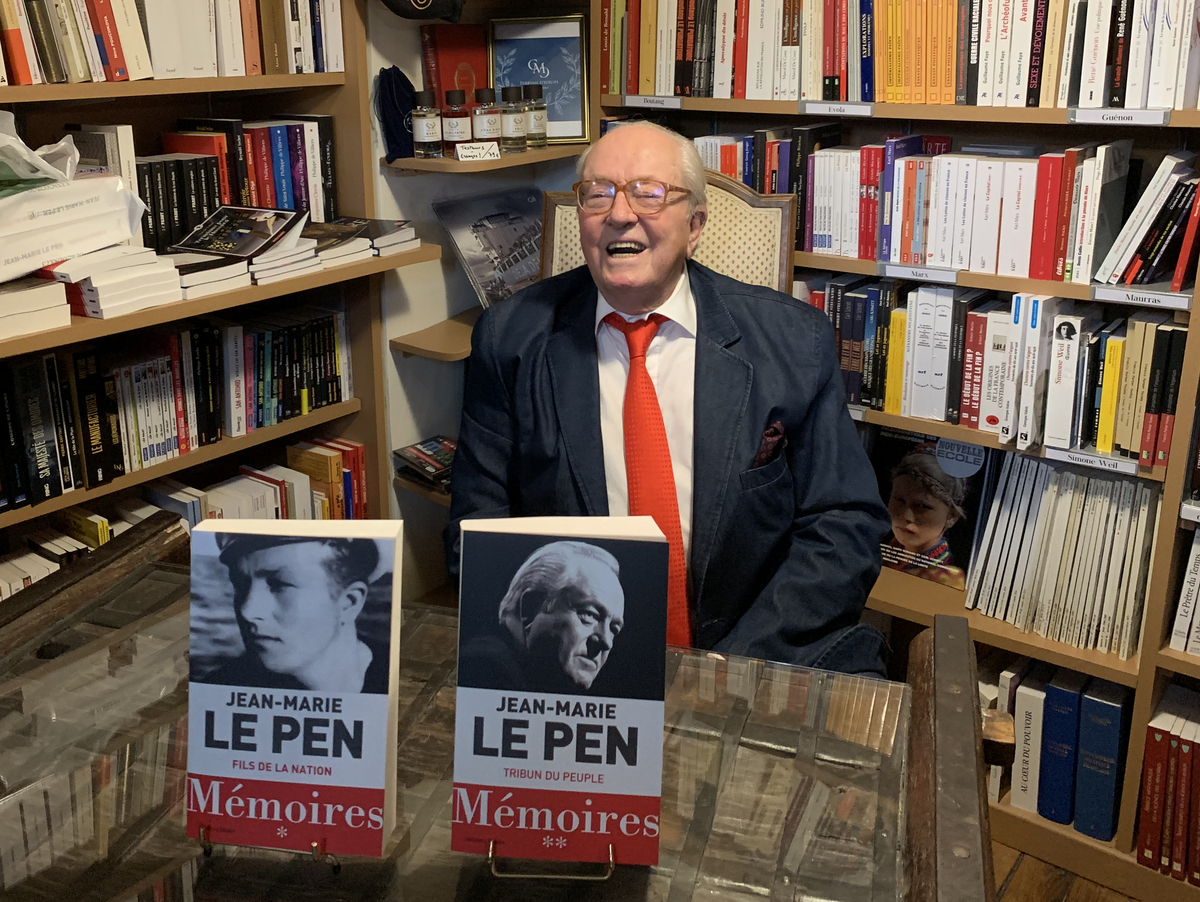

The founder of the National Front was once Europe's most famous far-right politician.

The founder of the National Front was once Europe’s most famous far-right politician.

In Lyon there were fireworks. In Marseille, people popped champagne in the old harbor. In Paris, posters bore unprintable slogans. You might think that all these celebrations were the work of fringe groups or migrants to whom Jean-Marie Le Pen had promised a «good life». Yes, they were there. But no — it was perfectly mainstream French citizens, students at the prestigious Sciences Po, future journalists and political scientists, who said utterly indecent things on camera.

Le Pen represents a kind of contradiction that France is, shall we say, embarrassed by. No one wants to admit that they support the far-right party he founded, the National Front, or the National Rally, which has evolved from Le Pen’s original structure with a few upgrades. Showing support for the NF’s ideas, let alone voting for them, has long been considered shameful. But people don’t reach the second round of an election for nothing.

This second round happened in the 2002 presidential election, when Jean-Marie Le Pen ran against Chirac in the final stretch. Of course, Chirac won by a landslide — but only because… well, it’s considered improper to vote for Le Pen. But people did it anyway. Some say Macron was similarly elected because voters didn’t want to support his opponent, Marine Le Pen, in the second round — just because of the Le Pen name. So in a way, he owes his presidency to Jean-Marie.

Jean-Marie never bothered with France’s so-called red lines and norms of decency. The Holocaust? «We don’t know». Gas chambers in concentration camps? «Yes, something like that happened, but it was just an episode in history». (He was dragged through the courts for years for this remark.) The occupation of France? «Nothing inhumane there». The Americans? «They’re not a nation, they’re just hybrids». And so on.

He practically lived in the courthouse. Every time Le Pen appeared on a broadcast, you could expect provocation. But he was invited, people watched and listened, and then they sued him for anti-Semitism and racism.

He left a fortune worth millions. Where did it come from? I’ve been to his mansion in Saint-Cloud near Paris a few times to film interviews — it’s lavish even by the standards of Barvikha (a famously wealthy suburb in Russia). His wealth has always raised many questions. He parried them by explaining that in 1976 he had inherited 30 million francs — an enormous sum at the time — from businessman Hubert Lambert, who was fascinated by radical right-wing ideas and even served on the National Front’s Central Committee. Doctors described Lambert’s condition as «physically and psychologically unstable, almost feeble-minded and susceptible to the effects of alcohol». A millionaire who lived with his mother, never took off his pajamas, and died of cirrhosis at age 42. Did Jean-Marie take advantage of a vulnerable man?

Le Pen’s slogan was «Les Français d’abord» — «The French first». The implication is that everyone else can wait. Is that true? For a man of the 1960s, a paratrooper who had served in Algeria, perhaps. But clearly he found a lot of like-minded people to form the National Front. He endured all the accusations of fascism, the countless lawsuits and everything else. Today these ideas seem completely absurd. History has moved on; he wasn’t a visionary. It’s impossible now to imagine a world shaped by his anti-Semitism, his hatred of immigrants and his Mussolini-inspired ideas.

Could today’s France do without migrants? Probably no more than Russia could. I’ve certainly never seen the sidewalks of Paris swept by someone with a fancy «de» in their last name. Is that Le Pen’s fault? Absolutely. He failed to foresee how Europe’s migration dynamics would develop. Is that also his fault? In a way, yes. Because in the end, the migrants took all those basic jobs away from the French, who, as Le Pen insisted, should always come first.

Of Le Pen’s three daughters, Marine took up her father’s banner — but she quickly realized that she couldn’t rely on old-fashioned slogans alone. First, she retired Jean-Marie and made him honorary president of the party. Then she rebranded it, changed its name, and made every effort to shed its «fascist» image.

Marine understood that her father’s ideas were half a century old and needed a new face. In today’s Europe, far-right ideas are in vogue, and Marine’s party wields real influence in the French parliament — even without an absolute majority. If her party doesn’t agree, there will be no resignations, no new government appointed, no budget approved — basically, nothing moves forward.

Nazi, fascist, xenophobe, Euroskeptic, protectionist, nationalist, anti-Semite, anti-American, manipulator — these are just some of the words the major international media used to describe the late Jean-Marie Le Pen. But I like one quote (from Politico, it turns out): «If he had been born 30 years later, he would be a friend of Donald Trump».