In Essequibo, Trump acted the American way — Maduro the Venezuelan

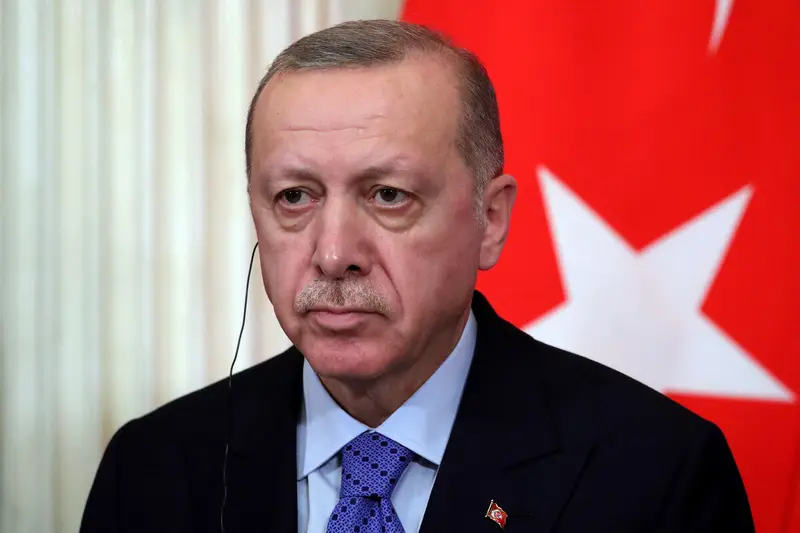

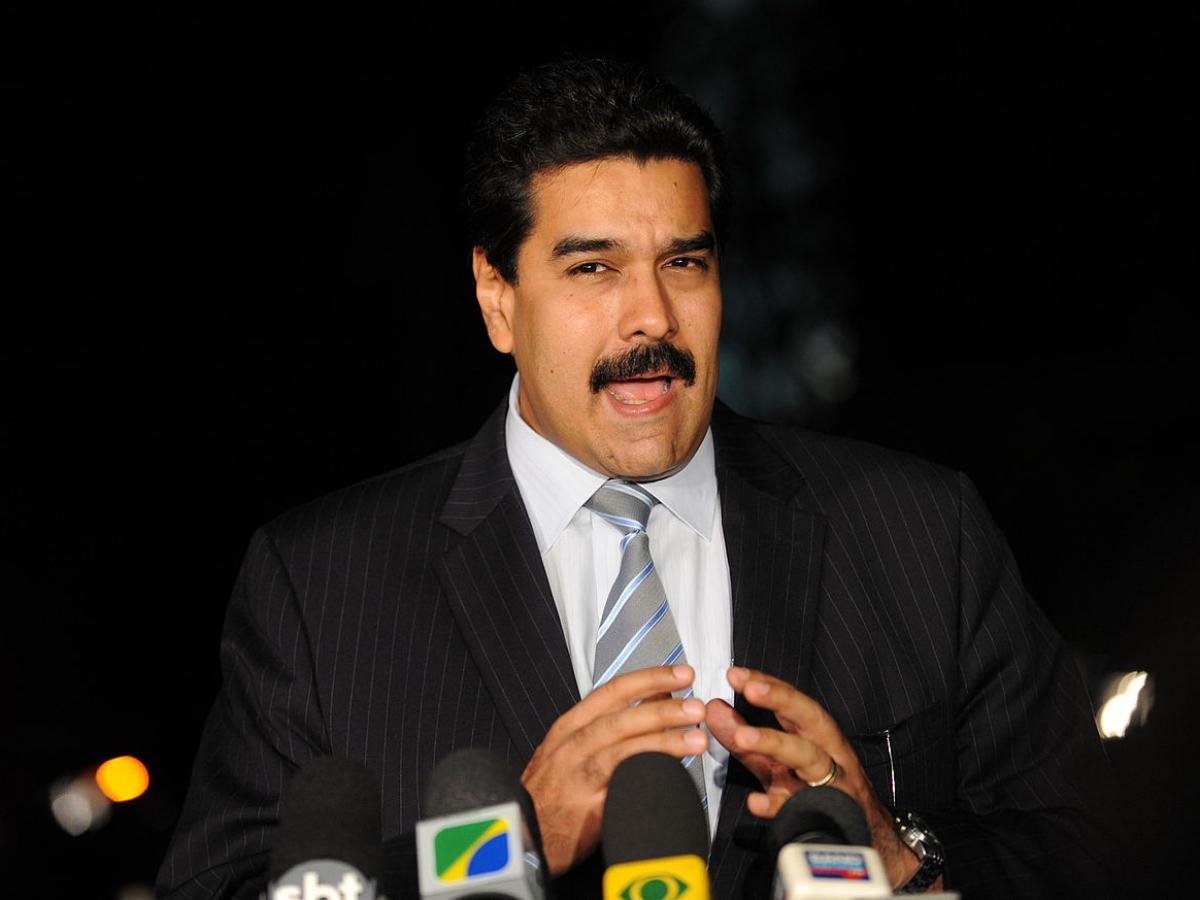

Two weekends ago, Venezuelans voted in the country’s 23 officially recognized states and, for the first time, in a newly declared one: Guyana Essequibo. On May 25, President Nicolás Maduro’s United Socialist Party of Venezuela claimed decisive victories in both the parliamentary and regional elections.

Voter turnout, however, was strikingly low — just 42.6% of eligible citizens cast their ballots.

According to official figures, the ruling party secured control over 23 of the 24 governorships and won more than 83% of the national parliamentary vote, further solidifying Maduro’s dominance across all branches of government. The centrist Democratic Alliance came in second with 6.25% of the vote, followed by the UNTC Unica alliance with 5.18% and Neighborhood Power with 2.57%. The remaining votes were either invalid or distributed among smaller parties.

To ensure «security» during the vote, over 412,000 military personnel were deployed nationwide — a common occurrence during Latin American elections, where far worse has occurred. According to Venezuelan intelligence services, authorities feared «external interference» in the election process and did not rule out possible armed provocations by the opposition, which boycotted the vote entirely.

The election results gave Maduro even more power. His party now controls all key institutions, from parliament and governorships to security services, at both the national and regional levels. Speaking at a rally in Caracas, Maduro hailed the outcome as «a victory for peace and stability» and praised the «outstanding role of the Bolivarian people» in achieving it.

Two of Maduro’s closest allies secured parliamentary seats: his wife, Cilia Flores, and party leader, Jorge Rodríguez.

An intriguing coincidence occurred in early May when Maduro visited Moscow while U.S. presidential envoy Richard Grenell held closed-door talks with members of the Venezuelan government in Antigua and Barbuda. According to Western media reports, the negotiations covered a wide range of issues, from migration and energy to the future of Maduro’s authoritarian regime.

What was not discussed, at least publicly, in either Moscow or Antigua, were Venezuela’s territorial claims to Essequibo.

Yet, even the opposition seized on the issue. María Corina Machado, one of the most prominent anti-Maduro figures, traveled to the disputed region by canoe to show her support for Venezuela’s claim to the territory.

Trump has his own ambitions, too. In March 2020, during his first term, the U.S. State Department proposed a «Democratic Transition Framework» for Venezuela. The plan promised to gradually ease sanctions in exchange for forming a transitional government that included both Maduro loyalists and opposition members, with one key condition. Maduro had to step down and hand over executive power to a U.S.-backed multiparty council.

The plan failed, partly because of Washington’s insistence that Maduro relinquish power entirely.

Now, Trump is returning to the issue — again, on American terms. However, this time it’s set against the broader backdrop of U.S. rivalry with China and Russia in Latin America.

The first pressure tactic is suspending some of the sanctions relief that the Biden administration granted to oil companies. This opened the door to limited foreign investment and convinced Maduro to agree to presidential elections on July 28, 2024.

«If American politicians are serious about countering Chinese influence in the Western Hemisphere, they shouldn’t drive U.S. companies out of Venezuela and push Caracas into Beijing’s arms. That would be more effective than another rushed attempt at regime change», Foreign Policy commented.

Analysts argue that it’s time for a new deal between the U.S. and Venezuela — one that will require time to develop. According to some sources, Trump is prepared to spend the coming months rethinking his approach to the oil-rich nation, seeking to resolve his domestic economic missteps through foreign policy concessions.

China is far away. Russia is far away. But America is nearby. Sanctions will quietly fade, the opposition will be «dealt with», and Maduro will remain in power — at least until the next election. The U.S. will refrain from intervening, which will allow American companies to remain in Venezuela and protect their investments. That’s the White House’s current position.

«The parliamentary and regional elections held in Venezuela on Sunday were well-organized and free of violations», said Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova. But beyond words, what more can Moscow do?

The stakes are high. If negotiations in Antigua fail, the United States may return to a «maximum pressure» strategy. It has both the justification and the means to do so.

In an interview with The Guardian, Guyana’s President Irfaan Ali called Venezuela’s decision to elect officials to govern part of Guyanese territory «a full-scale attack on Guyana’s sovereignty and territorial integrity» and a move that «undermines regional peace».

The International Court of Justice, the UN’s highest judicial authority, ruled that Venezuela must «refrain from holding elections» in Essequibo while the territorial dispute with Guyana remains unresolved. Western governments have echoed this criticism.

Caracas ignored the warnings. Venezuela pressed ahead, effectively pushing Guyana into the United States’ embrace. The United States has a clear interest in protecting ExxonMobil’s multibillion-dollar investments in the region. The U.S. denounced the vote as a «sham», and the European Union reminded Caracas of the importance of avoiding political repression and election manipulation.

For most Venezuelans, Essequibo belongs to Venezuela. For most Guyanese, however, Essequibo is part of Guyana. Washington doesn’t care who owns what.

Now, it’s clear why U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio chose to include long-forgotten Guyana in his first visit to Latin America. The fate of Essequibo hangs by an oil-soaked thread, and the U.S. seems ready to cut it — even by military means.